Why Is Boeing Missing Out on Iran?

It is no secret that the leading Republican presidential candidate — Donald Trump – is no fan of the nuclear agreement struck between the United States, other major world powers, and Iran this past summer. But his reasons for being so opposed strike me as atypical amongst other Republican candidates and help teach us an important lesson about U.S. sanctions.

Speaking in Des Moines, Iowa ahead of today’s Republican caucus, Trump said this: “Iran is buying 114 planes from Airbus. Where is Boeing? Why couldn’t we make it so Boeing could sell planes to them?” According to Trump, Iran’s decision to purchase civil aircraft from French aircraft manufacturer (Airbus) rather than leading U.S. aircraft manufacturer (Boeing) is only further evidence of how bad the nuclear agreement truly is.

Berating the lack of parity between U.S. and foreign business when it comes to opportunities in Iran is not a typical complaint among Republican or Democratic politicians. But the more interesting issue, of course, is that – when we get to the substance of the matter – Trump is wrong in this particular case and for an important reason.

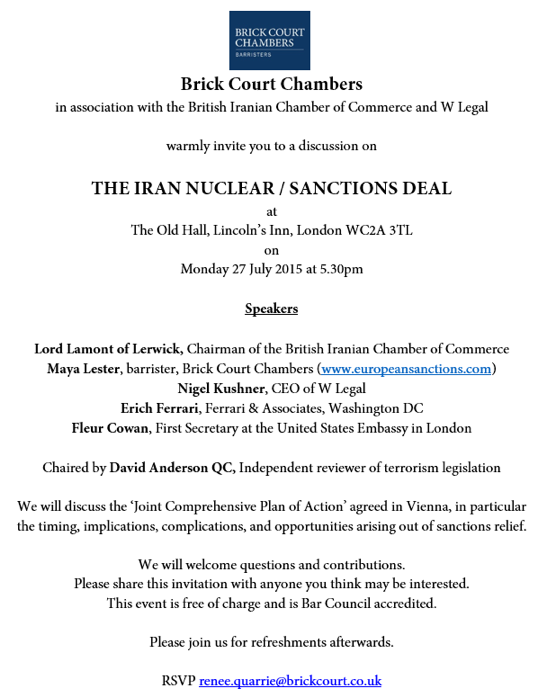

Under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (“JCPOA”), the United States was obligated to and did implement a favorable licensing regime under which Boeing could sell commercial passenger aircraft and related parts and services to Iran under certain restrictive conditions. This means that Boeing can apply to OFAC for a license to sell commercial passenger aircraft to Iran – as well as related parts and services – and that license application will be reviewed with a presumption in its favor.

Some might counter that this Statement of Licensing Policy (as it is known) created unfairly onerous conditions for Boeing in comparison to its foreign competitors, as it is still required to pass through the procedural hurdles of procuring a license from OFAC and ensuring that it is compliant with whatever restrictive conditions OFAC lays down in said license. But that argument is also in error, insofar as Airbus and other foreign aircraft manufacturers will often operate under the same conditions when it deals with Iran for one simple reason: almost all major commercial passenger aircraft – particularly in the West – contain more than 10% U.S.-origin goods or technology by value and thus are subject to the comprehensive U.S. trade and investment embargo with Iran as much as their U.S. counterparts.

Pursuant to 31 C.F.R. § 560.205, the re-exportation from a third country, directly or indirectly, by a non-U.S. person of any goods, technology, or services that have been exported from the United States is prohibited if (1) undertaken with knowledge or reason to know that the re-exportation is intended specifically for Iran or the Iranian government; and (2) the exportation of such goods, technology, or services from the U.S. to Iran was subject to certain export license requirements. This sanctions prohibition applies to all goods or technology that have been incorporated into a foreign-made product (say, an airplane) outside the U.S. if the aggregate value of such goods and technology constitutes 10% or more of the total value of the foreign-made product to be exported from a third country to Iran or the Iranian government. In other words, because most (if not all) major commercial passenger aircraft manufactured in the West contain 10% or more U.S.-origin goods or technology, the exportation of such aircraft from a third country to Iran or the Iranian government is subject to the sanctions prohibitions of the Iranian Transactions and Sanctions Regulations (“ITSR”) and would require a license from OFAC prior to export.

From what I have heard (and for this reason), Airbus worked in close coordination with Boeing and other U.S. companies to procure the necessary licenses from OFAC to ensure that it could fulfill its contract for the sale of 114 commercial passenger aircraft to Iran over the next several years. There might not be perfect parity between Boeing and Airbus when it comes to selling planes to Iran, but there is something close to it.

Why, then, did Boeing not take up the business? Most likely, it was a commercial decision that Boeing made in light of the substantial reputational risks that remain in doing business with Iran. Considering the fact that Iran has publicly stated that it is seeking 400 new commercial passenger aircraft over the next decade, Boeing executives might have understood that there was no particular advantage to being first in line – and perhaps some serious disadvantages should the nuclear agreement run into trouble not far down the road. As such, Boeing might well remain confident that it will get substantial business from Iran when the time is more appropriate.

But herein lies a key lesson: While the U.S. trade embargo with Iran prohibits U.S. parties from engaging in most transactions with Iran or Iran-related parties, it is sometimes the case that U.S. companies fail to pursue even permissible transactions due to the perceived reputational risk of being seen doing business with the Islamic Republic. We see this – for instance – in the relative lack of movement by U.S. tech companies with regard to General License D-1 – which permits the sale of personal communications technologies and other goods to Iran (such as iPhones; tablets; laptops and the like) but has been almost exclusively utilized for the export of free software. Now, we see it with Boeing as well in the sale of commercial passenger aircraft to Iran or the Iranian government.

For more than two decades – if not longer – U.S. companies have conducted virtually no business with Iran or Iran-related parties, and that has ingrained in them the calculus that doing so, when legally permissible, contains substantial risks with at best uncertain benefits. So long as that calculus prevails, we can expect more “missed opportunities” when it comes to potential U.S. business dealings with Tehran.

In one regard, Donald Trump is right that there exist serious inequities between U.S. and foreign companies when it comes to pursuing trade-related dealings with Iran. But, in another regard and in the specific comparison between Boeing and Airbus especially, his diagnosis of where those inequities originate from is incorrect.